Lithium Iron Phosphate (LFP or LiFePO₄) chemistry has become the backbone of modern Battery Energy Storage Systems (BESS), especially for grid‑scale, commercial, and renewable‑integrated applications. Its advantages—thermal stability, long cycle life, and improved safety—make it a preferred choice over other lithium‑ion chemistries.

However, “long life” does not mean “no degradation.” Even LFP batteries degrade over time, and the rate of degradation is highly dependent on how the system is designed, operated, and maintained. In many real‑world installations, sub‑optimal operating strategies shorten battery life far more than cell chemistry limitations.

This article examines the key variables impacting LFP‑based BESS degradation, combining fundamental degradation mechanisms with LFP‑specific behavior and practical operating guidance.

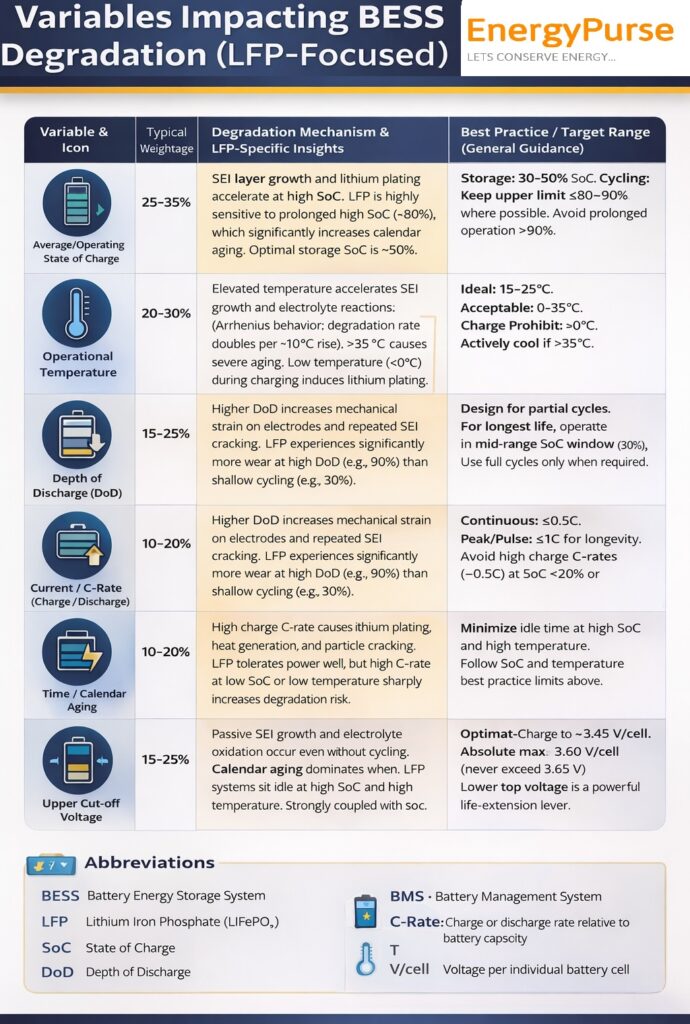

1. Average / Operating State of Charge (SoC)

Typical impact weightage: 25–35%

Average State of Charge is the single most influential variable affecting LFP battery aging. Degradation accelerates significantly when batteries are held at high SoC for prolonged periods. At elevated SoC, the Solid Electrolyte Interphase (SEI) layer grows faster, consuming cyclable lithium and increasing internal resistance.

Although LFP chemistry is structurally stable, it is particularly sensitive to calendar aging at high SoC, especially above 80%. Systems designed to sit fully charged—such as backup or poorly scheduled energy storage—often experience faster‑than‑expected capacity loss.

Importantly, this degradation occurs even without cycling. A battery stored at 100% SoC in warm conditions can age faster than one that is cycled daily but kept within a moderate SoC window.

Best practice:

- Storage SoC: 30–50%

- Normal cycling upper limit: ≤80–90%

- Avoid extended dwell time above 90% SoC

- Treat high SoC as a short‑duration operating state, not a resting state

2. Operational Temperature

Typical impact weightage: 20–30%

Temperature strongly governs electrochemical reaction rates inside the cell. Elevated temperatures accelerate SEI growth, electrolyte oxidation, and gas generation. Degradation follows Arrhenius behavior, meaning reaction rates roughly double for every 10°C increase in temperature.

Sustained operation above 35°C can dramatically reduce LFP battery lifetime, even if SoC and cycling are well managed. Thermal stress also amplifies the effects of other degradation drivers such as high voltage and high C‑rate.

Low temperatures introduce a different risk profile. Charging below 0°C slows lithium intercalation, increasing the likelihood of lithium plating on the anode—an irreversible and highly damaging process.

Best practice:

- Ideal operating temperature: 15–25°C

- Acceptable operating range: 0–35°C

- Charging prohibited below 0°C

- Deploy active cooling or HVAC systems when ambient temperatures exceed safe limits

3. Depth of Discharge (DoD)

Typical impact weightage: 15–25%

Depth of Discharge defines how much of the battery’s usable capacity is cycled in each operation. Higher DoD increases mechanical strain on electrode materials and accelerates SEI cracking and reformation.

LFP cells show a clear relationship between DoD and cycle life. For example, operating at 90% DoD can reduce cycle life by several multiples compared to shallow cycling at 30–40% DoD. While LFP is more tolerant than other chemistries, deep cycling remains a significant wear driver.

From a system‑level perspective, many BESS applications do not require full cycles daily. Designing operating strategies around partial cycling can significantly extend usable life.

Best practice:

- Target mid‑range SoC operation (30–70%)

- Use deep discharges only when economically or operationally justified

- Prioritize shallow, frequent cycles over deep, infrequent ones

4. Current / C‑Rate (Charge and Discharge)

Typical impact weightage: 10–20%

C‑rate determines how quickly energy is moved into or out of the battery. High charge C‑rates increase internal heating, lithium plating risk, and mechanical stress within electrode particles.

LFP chemistry is known for good power capability, but this tolerance has limits. High charge rates combined with low SoC or low temperature are especially damaging. Even when no immediate failure occurs, accelerated capacity fade and resistance growth follow.

Discharge C‑rates also contribute to thermal stress, particularly during sustained high‑power operation.

Best practice:

- Continuous charge/discharge: ≤0.5C

- Short‑duration peak operation: ≤1C

- Avoid fast charging when SoC <20% or temperature <10°C

5. Time and Calendar Aging

Typical impact weightage: 15–25%

Calendar aging refers to degradation that occurs regardless of cycling. Passive SEI growth and electrolyte decomposition continue as long as the battery exists, and their rate depends strongly on SoC and temperature.

For many LFP BESS installations—especially backup, reserve, or under‑utilized assets—calendar aging dominates total degradation. Systems that sit idle at high SoC and high temperature often lose capacity faster than actively cycled systems operated within controlled limits.

Best practice:

- Avoid storing batteries at high SoC for extended periods

- Actively manage standby SoC levels

- Maintain temperature control even during idle periods

6. Upper Cut‑Off Voltage

Typical impact weightage: 10–15%

Upper cut‑off voltage directly influences cathode stress and electrolyte oxidation. In LFP systems, charging to slightly lower voltages can produce disproportionately large gains in lifetime.

Every reduction of approximately 0.1 V per cell below the maximum significantly reduces degradation stress. While higher voltages increase usable capacity, the trade‑off in accelerated aging is often not economically justified.

Best practice:

- Recommended charge voltage: ~3.45 V/cell

- Absolute maximum: 3.60 V/cell

- Never exceed 3.65 V/cell

- Use lower top‑of‑charge voltages as a strategic life‑extension lever

7. Cell Balancing and Uniformity (System‑Level Factor)

Typical impact weightage: 5–10%

Cell imbalance is a silent but critical degradation accelerator. Poor balancing causes some cells to experience over‑voltage or over‑discharge, leading to localized aging and premature pack failure.

LFP’s flat voltage curve makes voltage‑based SoC estimation challenging, increasing reliance on accurate sensing and a robust Battery Management System (BMS). Inadequate balancing logic or low‑precision hardware can undermine even well‑designed operating strategies.

Best practice:

- Use high‑accuracy BMS with reliable SoC estimation

- Implement top‑balancing during controlled full charges

- Ensure balancing near the upper voltage knee (~3.45 V/cell)

Conclusion: Chemistry Enables Life, Operations Decide It

LFP chemistry provides an excellent foundation for long‑life energy storage, but operational discipline determines whether that potential is realized. State of charge management, temperature control, partial cycling, conservative voltage limits, and robust system‑level controls can collectively extend BESS life by years.

For developers, operators, and asset owners, the key takeaway is clear: degradation is not just a materials problem—it is an operational one. Thoughtful system design and intelligent control strategies are the most powerful tools available to maximize performance, reliability, and return on investment in LFP‑based BESS.

For understanding technical insignt on PVsyst report Click here